Inspirational Critique

“Don’t tear me down. Why don’t you give me somethin’ helpful I can work with? Instead of talkin’ shit and making mean expressions,” he sings, accompanying himself on electric piano.

There’s been a lot of trash talking the Zeros. The Zeros! Some of us gave this decade the best years of our lives. Some of us were sexy during the Zeros, and had multiple partners at once; some of us fell in love, got married; some of us made beautiful music together; some had loving pets; some stopped watching TV; some of us cooked; some made art, and some of it was good; we all got older, and, if we managed not to die, wiser. So, wise up. Stop acting like we aren’t supposed to be dissatisfied. It’s not a burden to be critical of the circumstances of one’s existence: it’s awesome, and banal, and it’s the situation in which we find ourselves, together.

“Don’t tear me down, and I won’t make you feel bad to make myself feel good. I’ll give you somethin’ you can use to make improvements. Help me grow and I’ll return the favor. Face me critically but full of positivity.”

We return to the term ‘critique,’ because it can be inspirational. For those of us who attended and/or taught in art schools during this decade and/or others, there is ritual and revelation in the word. It describes a moment of reckoning! (“I have a critique today,” she said, breathlessly. She was defenseless, exhausted and hungry, when the group encircled her object, which inspired a stuttering cascade of concurrences and rejections.) In it’s active form, critique is the passing of judgment upon the quality of a work; in order to make this judgment, it is considerate to have a method for organizing one’s responses; and a theory to inform the method. There are those who survived art school and never want to hear the word again, but this reaction is based on a misunderstanding. ‘Crits’ (elides with the condition ‘critical’) can feel like a mortal wound, self-inflicted, accidental, or purposefully torn open by a sadistic classmate. Crits are never good; but a good critique could save the (art/life) world.

His voice is joined by harmonies: “If we’re open about it, when institutional thought is ruptured, an inspirational critique can result. A moment in which, for a second, all is questioned, allowing understanding of the situation that opens itself to new possibilities.”

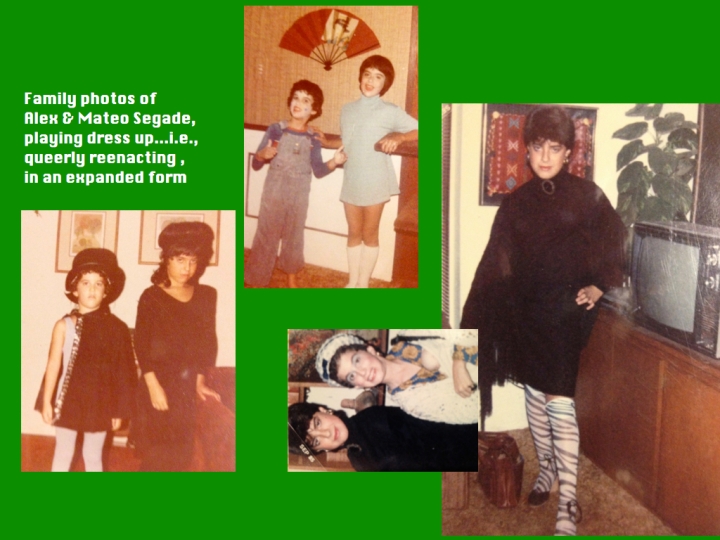

We are embarrassed by the regime that occupied the US for eight years. We are embarrassed by the plutocracy that dominates the art world. As long as art is expensive stuff, this will continue, and though it’s not-new, critique is a means toward another order of things. One may worry the boards of museums have hijacked these places in order to improve the value of their own collections. Without commodification, we would escape the capitalist trap, but alternatives to commodities, such as performance art, can also be used to move merchandise. When performance artists become celebrities, they take on the aura of the commodity, and when celebrities become performance artists, the hegemony of the fame/wealth axis is entrenched. We imagine an exception: un-collectable art by no one in particular. Hence, a useful complication is collaboration: by undermining the authority of the signature/brand, we forge a collective identity that cannot be collected. Collaboration must be critiqued too: museums increasingly support collaborative projects and so are imbricated within these artistic productions. Everyone is implicated: artists become collaborators in an uncomfortable sense: they are working for a regime. Many artists who mobilize critique toward liberation fashion themselves the resistance, yet our circumstances are such that artists must collaborate with the establishment in order to be seen/heard. Political art, sold in galleries or exhibited in biennials, is not a popular front. It is a luxury good. Thanks to the critical space art objects must occupy to enjoy their status, critique is a roommate of paintings. The self-inflicted mandate of the institution to critique itself allows money for projects that address this complex. Money seemed to die this year, yet artists haven’t disappeared, and neither have rich people. We have a live/work space that can accommodate both, but the lease must be re-negotiated regularly. The privileged are often the audience for the demands made by artists, and though we may participate in protest, we find ourselves saving up for cute outfits to wear to parties where the deciders promise a temporary piece of consecrated real estate, a wall upon which to hang a note with the cleverly hidden message: “End the War, Help the Poor.”

All together now: “La la la la La la la la la la la la la la la la la la la La la la la la la la la la la la La la la la la la la la la la la la la.”

The inspirational is an embarrassment that shocks the affected into the productive aspiration to modify behavior. Inspiration suggests our own condition is conditional. Critique is motivated by and towards inspiration. Inspirational critique flourished in the Zeroes (thanks, in part, to the clarity of opposition to it), and will continue into the Teens, hopefully. The most inspirational aspiration is the conditional phrase, “I could love you,” which, when sung aloud, becomes a refrain worth repeating.

leave a comment